Microwork: An introduction

According to contemporary discourse, artificial intelligence (AI) is exempt from human action and superseding physical infrastructures. However, recent studies on AI’s materiality recognize the immense network of natural resources and human labour that spans the entire planet. With our current resources, we can create, sustain, and regulate intelligent machines. From the extraction of resources to the treatment of information, the creation and distribution of technology to the disposal and recycling of outdated devices, artificial intelligence requires workers at every step.

In this context, microwork involves workers that provide and transform data destined to train and improve machines. These independent contractors work remotely and perform fragmented tasks – often requiring just a click – through online digital platforms. Their actions are essential for automated and intelligent systems since they play a part in the learning and correction of these systems, sometimes even impersonating these systems when they fail to provide results.

One of the first and best-known microwork platforms, Amazon Mechanical Turk, was named after an 18th-century automaton that toured throughout Europe, playing with—and even defeating—individuals at chess. In reality, and unknown to spectators, a concealed human player operated the automaton from within. Thus, much like the Mechanical Turk, microwork platforms create the illusion of automation by outsourcing the labour of their workers and rendering their actions hidden to the public. This “invisibilization” is part of an ongoing historical trend that includes 19th-century pieceworkers who effectuated small tasks from their homes for factories, or human computers that provided calculations for research institutions.

Mechanical Turk

Pieceworkers

Human computers

NASA “Computer Room”

Example #1: Content Moderators

Every second, web users upload an incredible amount of digital content to platforms, including video, audio, and images. Many companies deploy algorithms to detect and remove inappropriate content posted online. However, automated systems are oftentimes incapable of identifying it. If required, humans need to step in, review these posts, and remove them. These workers often suffer from intense psychological distress due to the nature of the content they are evaluating which, in some cases, includes examples of extreme violence and exploitation. Big technology companies outsource this labour to other companies, but these workers also operate through microwork platforms. As independent contractors, these workers are not entitled to psychological help through their employers. In some cases, confidentiality contracts forbid workers from discussing the nature of their work.

What is a platform?

Since microwork often involves externalized workers who can operate from anywhere in the world with an internet connection, companies rely on digital platforms to coordinate the offer and demand of work. In general, platforms are programmable digital infrastructures that exchange data between different users. They include social media websites like Facebook or e-commerce companies like Amazon.

Some of these platforms specialize in labour exchanges, including freelancing sites like UpWork and on-demand apps like Uber. From a labour transaction and geographical scope point of view, not every platform is the same. Some platforms allow complex activities, while others outsource fragmented tasks; workers may perform tasks bound to specific geographic locations, while others can work online. In an ecosystem of platform labour, microwork platforms are web and crowd-based. Requesters allocate the same tasks to a multitude of users around the world.

Example #2: The “Microtasks”

The French DipLab project identified the following tasks available on microwork platforms:

• Data entry

• Image labelling

• Document digitization

• Survey responses

• Content moderation

• Software test

• Product classification

• Web searches

• Voice recording

• Translation

• Transcription

Working conditions

Microwork platform workers are a hidden population due to the nature of their jobs, which makes them difficult to reach. Research on online work, including micro-tasking but also other types of remote freelancing, suggests that the supply and demand of labour is often—but not always—distributed between high-income countries and nations in development. The demographics and geographies of micro-work change depending on the platform. For instance, workers of Amazon Mechanical Turk are primarily male and located in the United States and India. At the same time, those working for French platforms are predominantly women and located in France and francophone areas of Africa.

In most cases, the people who operate these platforms are not considered employees or workers, but independent contractors. Therefore, they lack the social protections often tied with employment such as fair and guaranteed income. Nonetheless, workers value the flexibility of platforms which allows them to work remotely from anywhere in the world, and the revenues from these platforms are, in many cases, essential, even as secondary sources of income.

Online platform work is also characterized by superfluity and fungibility. In other words, workers feel that they are easily replaceable due to the large number of workers in relation to the offer of tasks, and platforms rely heavily on reputation scores and evaluations to distribute these tasks. Workers are constantly reminded that they can be fired quickly and at any time, as platforms can delete their accounts easily and without recourse. The intermediation of platforms further alienates workers, as some ignore the identity of their employers are, and the majority don’t know the function of their work.

Example #3: “Deep Labour” Platforms

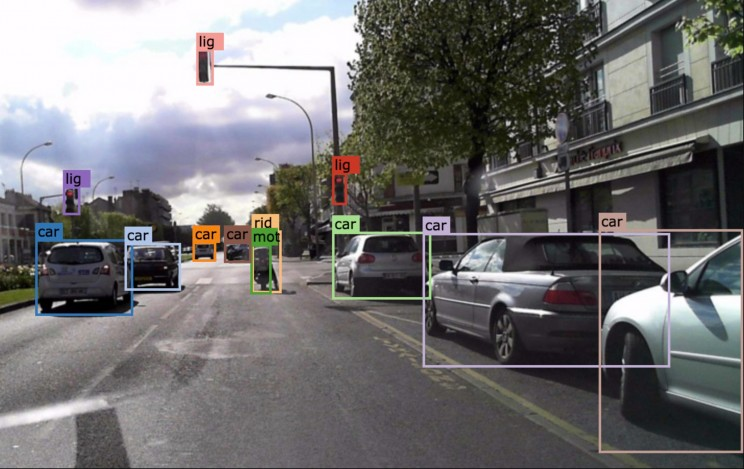

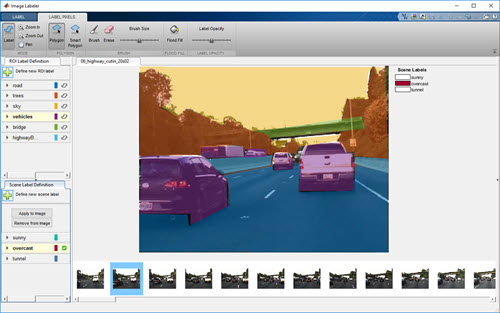

In recent years, there has been an emergence of new microwork platforms that shift away from the business model of earlier platforms like Amazon Mechanical, which allowed different kinds of tasks. These platforms specialize in a particular sector, such as exclusive training for artificial intelligence systems. Moreover, while non-specialist platforms coordinate the advertisement of jobs and the recruitment of workers, these newer platforms outsource these elements, making their operations challenging to trace. Some scholars classify this type of platform as “deep labour.” Take, for example, platforms that focus on training algorithms for self-driving cars that request their workers to provide image classification, object detection or tagging, landmark detection, or semantic detection. Daily internet users provide similar data when they are asked to detect objects through ReCAPTCHA to prove that they are not robots. However, self-driving cars require more complex tasks fulfilled by microwork.

Tagging for self-driving cars

Segmentation for self-driving cars

Recent Initiatives

Due to geographical dispersion and lack of face-to-face communication between workers, achieving collective organization—and unionization—in online labour contexts remains difficult. In the case of microwork, workers mainly rely on online communication. For instance, 90% of workers on Amazon Mechanical Turk use forums to communicate. In the past, workers have successfully pushed for better working conditions, even on their own. One of the best examples of worker and academic action towards fair online labour is Turkopticon, which allows Amazon Mechanical Turk workers to rate their requesters. Before its creation, workers were the only ones being evaluated by their employers, creating a significant imbalance of power. Thanks to this initiative, workers can rate requesters in terms of communicability, generosity, promptness, and fairness.

Regarding regulation, it is challenging for governments to address microwork platforms due to the transnational nature of their operations and the difficulty of assessing their transactions. In some cases, governments and policymakers, notably in developing countries, welcome online labour platforms as a means of reducing unemployment. So far, regulatory examples of labour platforms include mostly location-based ones like Uber instead of web-based cases.

Example #4: The Fairwork Foundation

The Fairwork Foundation is a non-profit that ranks platforms according to ethical labour principles. Modelled after the Fairtrade Movement, it aims to create awareness about consumers, platforms, and policymakers on the working conditions of platforms and how they affect their workers. The Foundation rates labour platforms, including microwork platforms, based on principles of fair play, working protections, contracts, and management.

- Microwork: An introduction - February 20, 2020