What’s next: Investigating personal futures

I found the microwork workshops to be highly supportive of the participants’ commitment to convey strategic perspectives to policymakers. After reflecting on the findings, I make a case for the next steps – a focus on the personal futures of microworkers. How might they see themselves in their futures?

– Maggie Greyson, Futures Present

When planning the microwork multi-session workshops, our team prioritized methods that drew a robust image of the future. We also sought strategic perspectives, that highlighted economic, social, and cultural impacts. Although microtasking was the intended focus of the inquiry, it resonated with peoples’ experiences at work.

This got me thinking. How could we go deeper? Designers, policymakers, and stakeholders often have standard employment relationships. Could they be able to “walk a mile” in the shoes of people who have rejected standard employment by choice, or been excluded through systemic inequities?

What’s happened so far

For two microwork workshops, we carefully curated groups with people from diverse backgrounds. For example, each group included at least one person under 29 years old with gig economy experience. Yet authentic microworker perspectives are missing in the first phase of the microtasking project.

So our team acknowledges the potential to go deeper by investigating personal futures.

A highlight of the workshops is the Toronto 2030 scenarios. They depict the futures of services, infrastructure, and education as they relate to microwork, and the gig economy. Also, they depict the public and private interests of four people. Most importantly, the implications and strategic perspectives of the scenarios can provide direct resources. It’s also influencing our direction and rate of change. As evidenced by the TWIG Microtasking Report 2020, the team achieved the rational aim of the workshop.

To do this well, the team developed workshops which included the experiential aim of prioritizing feelings of inclusion. Generating wisdom for the participants was also an important part of our workshops.

From the first point of contact to the last survey, we showed our participants just how much we value their contributions. All our microwork multi-session workshops crafted maximum participation and a diverse group of stakeholders.

We aimed to made everyone feel included.

Individual experiences and how they might affect their interactions were taken into consideration. As a result, participants felt connected to the workshop and 28 out of 45 participants responded to the final survey; their responses were overwhelmingly positive.

Participant’s comments

Excellent session –wonderful facilitators, thoughtful framework and a great mix of stakeholders.

Interesting to learn more about microwork and an engaging process that made good use of time.

I found the experience to be very eye-opening and set the holistic view of microtasking.

Very positive and interesting.

I had such a good time attending both workshops. This is such a great initiative.

To accommodate diverse learning styles and expressions of ideas, we engaged participants on several sensory levels.

First, we designed activities for quiet reflection and sharing in pairs. Then, we got participants on their feet. Also, the workshop tools and sticky notes were colourful, and bright markers were used at each table. Colourful cards facilitated conversations and there were printed cards with expressive icons.

Meanwhile, some of the participants played with the toys, which introduced fidget tasks to simulate microtasks.

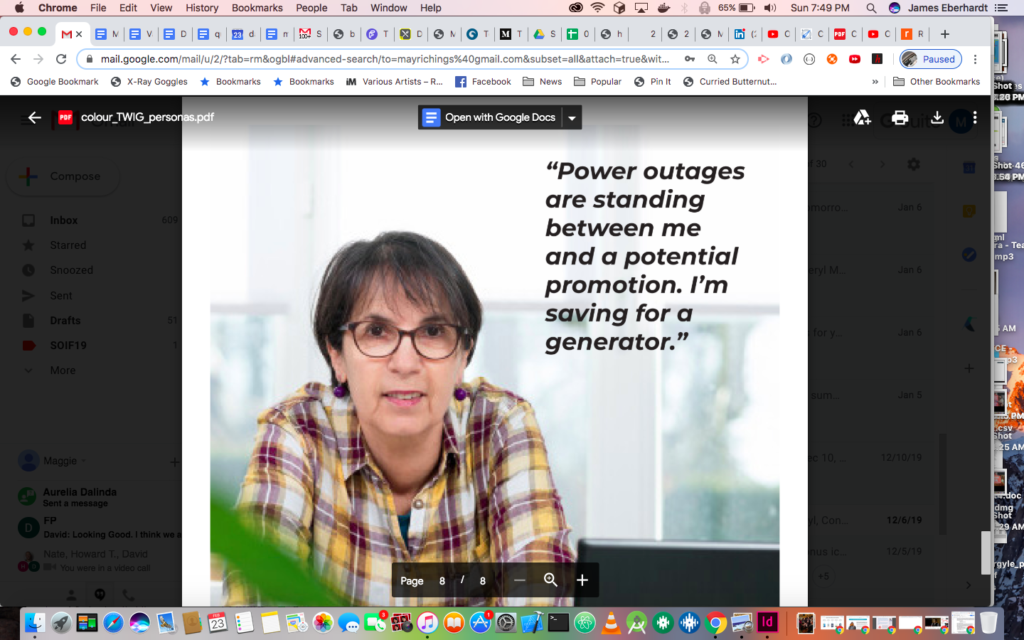

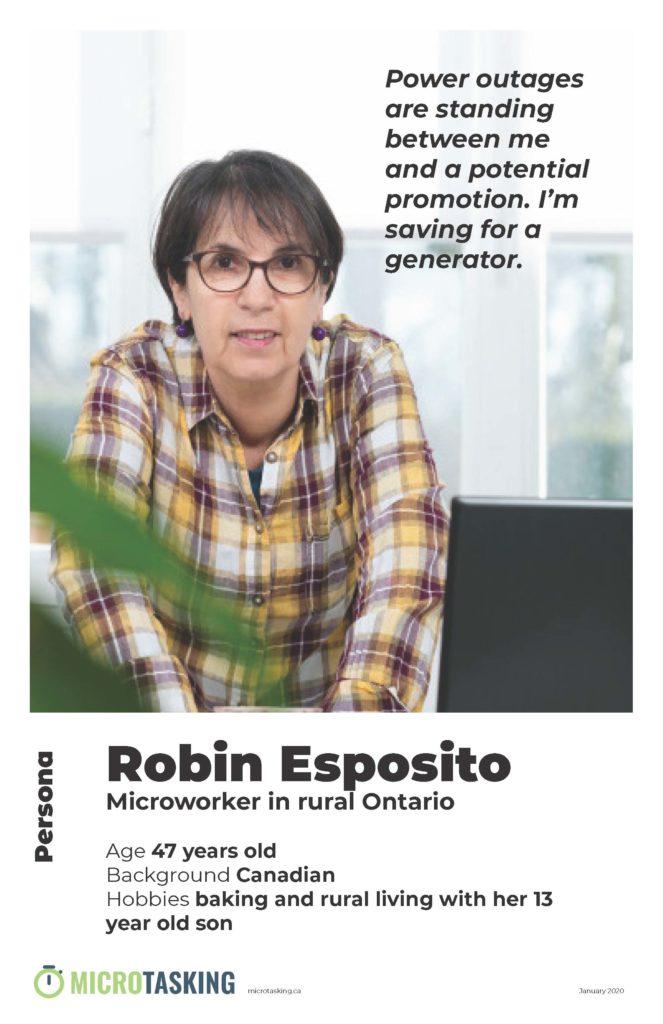

For the first workshop, each table contributed to the creation of scenarios and personas. For the second workshop, we printed large posters with bright pictures of the personas. Also, these posters included a few reminders of their personal context. All of the scenarios were brought to life with large colourful posters, which included graphic contextual images.

Most importantly, our foresight and participatory action research methods were well-received.

Thanks to the research methods, new insights have been put forward. The results, reports, and toolkits can help program designers, policymakers, and other stakeholders make sense of system-level futures. Especially the futures that will affect their work. But as one participant asked:

“This was great; what comes next?”

Personal futures and the expectations of tomorrow

The results of the September 2019 to January 2020 research and activities illuminate a gap. According to our recent findings, a technique that helps people consider the human experience of the future is needed.

Thinking long-term with the same level of detail as we have is challenging. As a result, we tend to assume that current events, looming forecasts about unemployment, and a lack of information will continue unabated. Our microtasking workshops also revealed an undercurrent of contemporary issues that bubble beneath the surface in everyday life.

A.I., bioethics, virtual reality, privacy, and free will and determinism are seemingly out of control issues. Unchecked, this lack of control can manifest as dystopian views of one’s own life in the future.

Through a broader horizon, and without the existence of current issues, the practice of foresight is an opportunity to think long-term.

However, we tend to run into stumbling blocks when we think long-term. Mental images become blurry. They don’t have the same level of context or feeling as they do in the present. We are attracted to menacing, dramatic stories in the news and entertainment.

There are no facts about the future. Because it hasn’t happened yet. So how will we ever make decisions? Anxiety is a barrier to reason. This anxiety impacts judgement about what people say they “will want” or “need”. We also think we will be less intelligent in the future than we are in the present.

Our visions portray more black and white dichotomies; Margaret Mead identifies this as work-play and jobs-no jobs. This dichotomy is connected to tempocentric way of thinking that keeps us locked in the present. By judging events on the basis of contemporary standards we create a bias. This bias makes it impossible to support one’s own preferred future.

However, we can overcome some of these tendencies. When researching microwork’s contribution to the future of work, researchers can benefit from activities that help participants adjust their expectations of tomorrow.

So a struggle is going on in this country. It has been going on now ever since the first hint of automation. (Automation) provoked our suspicions; it made us believe that we weren’t going to create enough jobs or increase productivity. Yet, we are going to be able to do that to an unlimited degree. Our (real) problem is how we’re going to devise a system where every individual’s participation in society creates dignity and purpose. Our society must have a rationale for distributing the results of its high productivity.

– Margaret Mead, Seminar on Manpower Policy and Program (Washington, D.C.: Department of Labor, January 1967).

Personal futures as a next step

An ethnographic design-research technique can help individuals adapt to change. Often, people aren’t given the opportunity to talk about their expectations of the future or challenge their assumptions.

Foresight is not a spectator sport. The person who imagines the future plays a part in creating it.

– Graham H. May, The Sisyphus factor or a learning approach to the future (1997).

Personal futures can add to our understanding of microwork while illuminating individual contributions to society.

Another crucial benefit is the illumination of peoples’ perceptions of success based on their well being. Since individuals are the experts of their life, there’s a place for understanding one’s “whole self”. Although it’s not just about the activities serving the work. In fact, microworkers already live in a system that is shaping the future.

Combining foresight and ethnography puts the person at the centre of inquiry. Personal futures identify one’s own assumptions about what they want. Yet this may be different than what you think “everyone” or “no one” wants.

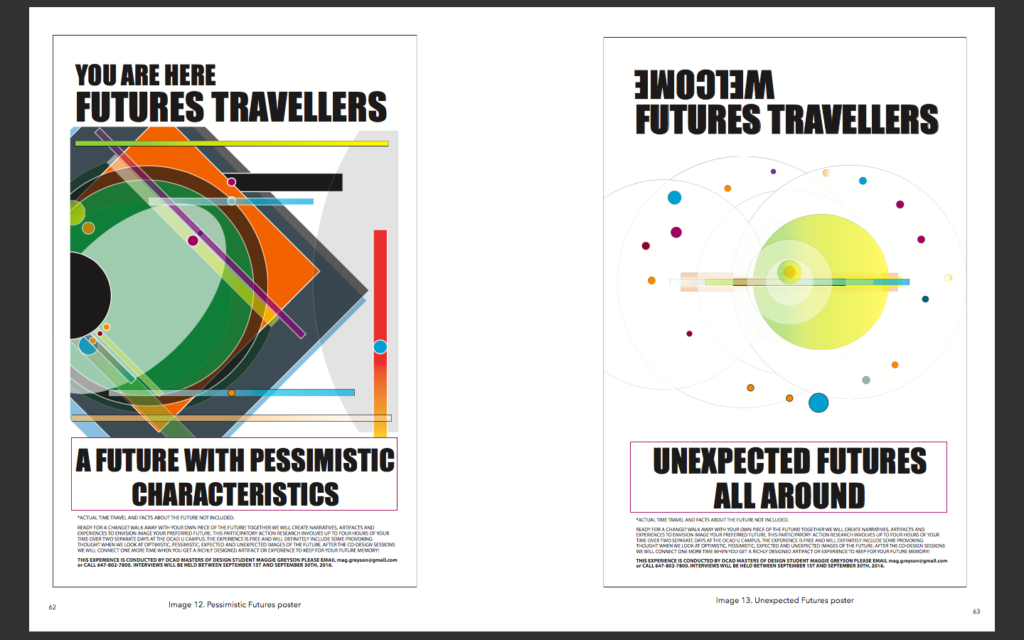

In 2016, I completed an exploration into the needs of people. Through this exploration, I reframed personal stories in the context of complex futures. The technique that emerged is called Making the Futures Present. It combines the activities of ethnographic research, the principles of experiential futures, and prototyping methods.

According to my research, personal futures techniques help people envision a preferred future.

For participants, this future starts at someone’s worldview and uses prototypes that fold back time. In the low-risk setting of a workshop, they can envision clearer images of the future.

With some authenticity, Making Futures Present provides a brave space where assumptions about the future can be explored. This experience helps people understand that some things will be consistent in the present reality. It also recognizes that there is a spectrum between preferable and undesirable futures.

Next steps

We were encouraged by the studies available and the research that is being done. Because the digitalisation of the economy is an important contribution to The City of Toronto’s focus on inclusive economic development. Also, it’s an important part of Statistics Canada’s initiatives.

On-the-ground research conducted by TWIG and the Workforce Planning Ontario network is a significant contribution to all future of work-focused studies. For instance, gathering personal perspectives from people with non-standard employment is a common approach to microworker workshops. Personal futures techniques could trigger a placemaking approach to participatory action research.

People involved in non-standard employment are a larger group than one might think.

At the first microwork workshop, one of the participants asked: “who here has what we would consider traditional full-time employment?” Hand after hand went up, as surprise rippled through the room. At least 75% of the people in the room identified with non-standard employment!

Non-standard employment as described by the ILO includes “temporary employment; part-time and on-call work; temporary agency work and other multiparty employment relationships. It also includes disguised employment and dependent self-employment.” It is the stock in trade of the gig economy and microwork platforms.

Statistics Canada released results from a study measuring the gig economy in Canada using tax data. The study found that from 2005 to 2016, the percentage of gig workers in Canada rose from 5.5% to 8.2%. For comparison’s sake, the ILO reports that the worldwide demand for online gig work has increased by roughly 20% per year.

Making Futures Present is an example of a personal ethnographic futures technique. Because it can harvest qualitative data about non-standard employment, gig work, and platform-based microwork.

This technique uses an activity sequence, which helps individuals pre-adapt to the future. Its tools are the imagination and existing knowledge.

Then the participant describes their expectations; what is unlikely, and what if things were even better or worse than expected. Answers reveal bias-based on the sources of their assumptions. There are no value judgements placed on experience. When referring back to the experiential aim in the microtasking workshop design, evidence from participants’ lives can help them have a realistic outlook on their decision making power.

Activities in personal futures add new human-centred dimensions to our assumptions about the future of work. When they engaging in an interactive workshop, a participant recognizes where they have agency. They also uncover where they have the skills to survive and thrive, and make decisions that align with their values. Most importantly, this technique highlights the values, goals, skills, and abilities that people treasure. Meanwhile, participants are learning exactly how they can hold their values into the future.

A personal futures workshop with individuals on the gig worker to microworker continuum offers insight, inspiration, and aspiration. However, the output also provides authentic but hidden perceptions that are vital if we are to design a system that gives everyone dignity and purpose.

Photo of people and their shadows by Kolar.io on Unsplash

- What’s next: Investigating personal futures - February 25, 2020